The Climate Footprint of Plastics: Search for Solutions in Asia, Europe, and the United States

Overview

When most people think of plastic waste they might picture discarded bottles on the ground or straws in the sea, but along the entire supply chain—from oil extraction and manufacturing to disposal—single-use plastic packaging waste is emitting carbon dioxide into our atmosphere. The Center for International Environmental Law estimates that without drastic steps to reign in plastic use, by 2050, up to 13 percent of our total remaining carbon budget will be used up by plastics. The International Energy Agency predicts that petrochemicals, including plastic, will account for 45% of the growth in oil and gas mining from 2018 to 2040. A growing number of researchers and activists are warning that the world must drastically reduce single-use plastic production and consumption to keep the earth from warming beyond the 1.5°C target.

At this China Environment Forum, speakers delved into market changes, policies, lawsuits and technologies critical to reducing virgin plastic resin and plastic waste. Starting with Carroll Muffett (CIEL) who outlined the often hidden sources of carbon emissions along the plastic lifecycle. Next, Von Hernandez (BFFP) highlighted the climate-plastic nexus in Asia and the efforts of groups on the ground to counter the false solutions being promoted by corporate polluters to justify the continuing production and use of throwaway plastic. Alice Mah (University of Warwick) shared her research into the environmental and social impact of the growing petrochemical pollution in China’s Yangtze River Basin. Rosa Pritchard (Client Earth) reported on her organization’s work pushing for new laws that limit unnecessary single-use plastics and bringing legal cases in Europe that make plastic producers responsible for the environmental costs of dealing with plastic waste.

Selected Quotes

Carroll Muffett

“It's really important to recognize that these emissions are cumulative, they add up in the atmosphere and that means between now and 2050, the plastics life cycle could add fifty-six gigatons of carbon to the atmosphere. This is equivalent to thirteen or more percent of the Earth's entire remaining carbon budget in a 1.5-degree world. But as I emphasized, our estimates were conservative and the real picture continues to accelerate.”

“An even more insidious and potentially even more dangerous threat from that life cycle; plastics do not stop emitting once they leave our homes, once they leave our economy, once they enter the environment. Research has shown that plastics continue to emit greenhouse gases even when they are in the environment including high-impact greenhouse gases like methane. Beyond those direct emissions, however, there are now more than fifty-seven trillion particles of microplastics accumulating in the ocean surface and that number continues to grow.”

“Put more succinctly, what this evidence is showing is that the plastic crisis could be accelerating the climate crisis not only by contributing to and accelerating the emissions themselves, but by impairing the Earth's ability to store and sequester potentially enormous amounts of carbon.”

Von Hernandez

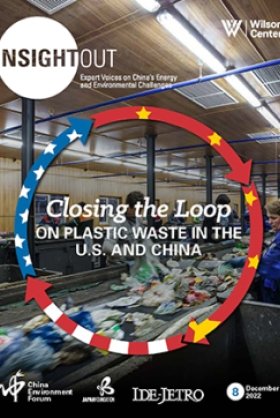

“Even industrialized countries like the U.S. and in Europe, they've been grappling with this issue of plastic for years. Except that they were able to hide it off and one way they've done that was by exporting what they used to call recyclables or recycling to China for decades until China I think three years ago decided to say no and put a stop to (the) importation of plastic waste. But the result has been a mad scramble for alternative destinations for the plastic waste coming from the west.”

“Through these approaches, exposing waste trade, doing brand audits, we are slowly trying to evolve or change the narrative around really what's driving this crisis. So it's not simply the countries that have been named but really looking at companies and manufacturers that are liable for this problem. It could be a mix of global as well as local companies.”

“Our top polluters keep talking about recycling, keep putting out pledges to improve recycling, and constantly failing those pledges every time, yet this is still the industry response.”

Alice Mah

“There's a dependency on these plants for work, and an increasing shift where the most privileged workers, those on the highest salaries live further away from the plants, and the migrants live closer to the plants and also work the more dangerous jobs. There was a very strong sense of frustration on the ground, there is this environmental protection hotline, but there's this overwhelming sense of (like) there's nothing they can do about it.”

“This is just quite striking in comparison to some of the U.S. examples where everybody knows about their health risks they're not contested. But there's no access to information there’s no scientific reports, the pollution is acknowledged by the state but they don't make that information available they don’t say it’s an occupational health risk explicitly it’s normalized as part of everyday life and even the NGOs are working in this context where they're trying to improve the environmental monitoring trying to work within the sensitivities around the political systems in pragmatic ways to help reduce risk but they're not thinking about the bigger issues about linking to climate linking to environmental justice.”

“At the end of the day what we want to see is really a shift in investments and focus on alternative delivery systems.”

“I think the problem is actually the same as it is in the U.S. and globally which is there is no recognition anywhere that we should scale back petrochemical production 58:10]. It's still seen as a growth mechanism and in the Chinese state it's a pillar and it's meant to be a drive towards, they use this language of self-sufficiency around being able to produce all their energy but also their own plastic commodities. I think it's evading attention due to more attention going to more obviously polluting sectors that are right next door like coal and steel even though petrochemicals are just as bad.”

Rosa Pritchard

“We have another very different workstream which is what we call plastics as a business risk, and this is really trying to make the case to companies and perhaps even more so to the investors in those companies and to the banks that finance those companies and the businesses that depend on single-use plastics like for example the big food and beverage companies and grocery retailing groups, that they face mounting financial risks arising from their dependence on single-use plastics, and these are linked to a very rapidly changing regulatory environment mounting consumer pressure of course and the reputational risk of being a company that's publicly associated and renowned for contributing to plastic pollution.”

“These risks don't just relate to plastic waste and plastic pollution, which are probably the most widely recognized and well-understood manifestations of the plastic crisis but also from the links between plastics and climate. So for example we talk about E.U. regulatory conditions which to date have shielded plastic producers from the carbon price and these are starting to be phased out, and obviously, fossil fuel markets are facing very uncertain market conditions, and we make the argument that plastic packaging is likely increasingly to embed the carbon price and to therefore represent an increased cost for these big users of plastic packaging.”

“At every point, we're trying to integrate those arguments into our work on these topics because we really want companies, investors, financial institutions, and governments and decision-makers as well to recognize that single-use plastics is really a piece of the fossil fuel infrastructure, and that is doesn't make any sense to have robust policies and laws that are tough on fossil fuels but remain silent and inactive on single-use plastics.”

Speakers

Carroll Muffett

Von Hernandez

Alice Mah

Rosa Pritchard

Hosted By

China Environment Forum

Since 1997, the China Environment Forum's mission has been to forge US-China cooperation on energy, environment, and sustainable development challenges. We play a unique nonpartisan role in creating multi-stakeholder dialogues around these issues. Read more

Science and Technology Innovation Program

The Science and Technology Innovation Program (STIP) serves as the bridge between technologists, policymakers, industry, and global stakeholders. Read more

Environmental Change and Security Program

The Environmental Change and Security Program (ECSP) explores the connections between environmental change, health, and population dynamics and their links to conflict, human insecurity, and foreign policy. Read more

Thank you for your interest in this event. Please send any feedback or questions to our Events staff.